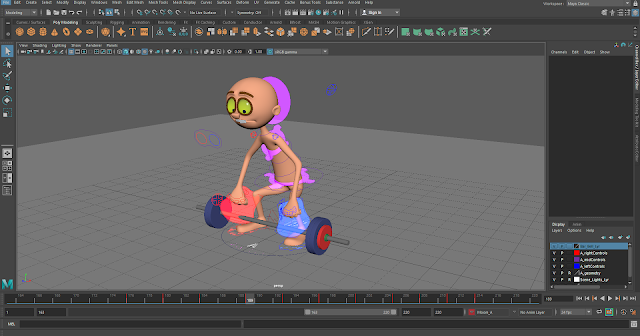

Last week's Maya lesson had us looking at breakdown poses for our weightlifting animation. This meant adding in four more poses before we move on to looking at anticipation and follow through and then cleaning up what we have with the graph editor.

Thursday 31 October 2019

Collaboration: Set Design (Part 5)

Before the studio moved on to storyboarding, we spoke about the different angles we'd be using; this meant taking a look at the other wall behind one of the characters. Since this is the only room featured over the course of the skit and not a great deal of it is shown, it didn't make sense to overcomplicate it further by introducing other tables or an extension to the room in the distance.

Wednesday 30 October 2019

Toolkit 2: Character Design: Session 4

In this week's character design lesson, we started to look at body language and gestures to help emphasise personality in our characters and drawings. We were split into groups and each group was given a list of prompts. From this, one person from the group at a time would get up and pose for the rest of us to draw.

After this, we had to pick one of the prompts and make a quick character design based on the pose, with the option to redraw one of the poses we'd drawn earlier or to use a new one. I chose the rockstar prompt and took a photo of Shannon in the pose to help me.

In the afternoon, we started to focus on our projects again. I was feeling somewhat lost in regard to the design of the main character, so I revisited the 1940's vinyl toy dog design somewhat using the image I'd already looked at of it online. I started by doing a quick copy of the head before starting to look at various different things such as what type of ears he'd have or whether or not he'd be anthropomorphic as opposed to a 'regular' dog.

I also looked at different animation styles I could think of at the time, such as anthropomorphic dog designs from Treasure Planet, Bojack Horseman, and The Amazing World of Gumball in particular. Another thing I had to consider was the rest of the prompt; not only is the character a vinyl toy, but they're also "scared of weapons"; after speaking to Justin, we decided that the dog character would suit this trait (since dogs tend to be scared of loud noises like fireworks, so it'd make sense if the character hated weapons like guns because of the noise). He'd also be much more reluctant to wield a weapon for this reason.

Justin also suggested that maybe the character isn't the gangster, and that this is more suited to the villain character. As I've played with the idea of having the "big shoot-out" and "entering the room prompts" being that of gangsters raiding some sort of back-alley bar, the hero character could actually be someone working in the bar and defending themself and the other people - therefore he would be dressed less like a detective and more like whatever his job is (a barman, someone playing an instrument like a pianist, a waiter, etc.).

I also carried on looking at the 'femme-fatale'-type character. This time, I began to consider other aspects of the 1930's-40's in her design including that of a 'toonier' style while still trying to make it work with the vinyl toy/plastic prompt. This involved looking at older animation styles like those from around that time like early Mickey Mouse cartoons and Betty Boop. I also looked at newer media that utilises the rubber hose style like Steven Universe or Cuphead. For the toy aspect, I looked at characters from Toy Story (in particular, the older-styled toys from Toy Story 4).

I think it'd be appropriate if the character had a painted on face as well as a lot of dolls and toys from the 1930's-40's have this kind of look.

I will work on refining these designs so I can move on to designing the villain and set sometime soon.

Monday 28 October 2019

Toolkit 2: Drawing: Session 4

We started off this week's life drawing session with five short poses. I tried to loosen up my drawings a little bit this time around, focusing less on detail and more on the marks I was making on the page alongside suggesting shapes with as few lines as possible.

We then moved onto some more poses wherein the model used more props.

After that, Simon advised us to pay close attention to facial features and how this can influence the mood or action of a piece as well as trying to capture the likeness of the model. Since I tend to shy away from faces as they're an area I'm slightly less comfortable in drawing, I found it to be good practice.

We did one more five minute pose after this.

Film Reviews: Monsters, Inc. (2001) and Linear Structure

Fig. 1: Theatrical release poster for Monsters, Inc. (2001).

This review will be examining the structure,

ending, and plot type of Pete Docter’s Monsters,

Inc. (2001) by looking at Syd Field’s three act structure, Gustav Freytag’s

five act structure, alongside closed, partial, and open endings and arch plots,

mini plots, and anti-plots.

Monsters, Inc. is centred around two

monsters, James P. Sullivan (or Sulley) and Mike Wazowski, and their line of

work in the city of Monstropolis as “scarers” in the titular factory. The city

is powered by energy harvested from the screams of human children; the children

themselves are believed to be toxic, and as the children are becoming harder to

scare, the city is threatened with an energy shortage. Mike and Sulley come

across a lost human child whom Sulley nicknames “Boo”, and they try to return

her home all the while being antagonised by rival and fellow scarer Randall

Boggs. By the end of the film, the company’s chairman, Henry Waternoose, and

Randall are revealed to have been forming a corrupt plot together, leading to

Sulley replacing Waternoose as the company’s chairman. The energy crisis is

resolved when laughter is found to be much more sustainable than screams, and

Sulley is reunited with Boo after Mike reconstructs her destroyed door.

The three-act structure proposed by

Syd Field originated in 1979 (Strathy, 2008), with each act representing an aspect

of the story: act 1 is the ‘Setup’, act 2 is the ‘Confrontation’, and act 3 is

the ‘Resolution’. Field’s structure, while following Aristotle’s structure of a

beginning, middle, and end, places an emphasis on two “important turning points in a story” (Strathy, 2008), which are known

as Plot Points 1 and 2 respectively. Field also makes mention that the middle

act tends to be the longest.

Fig. 2: A diagram of Field’s three-act

structure (2008).

As for the acts themselves, there is

usually a typical pattern followed by media that uses this structure. The first

act, as its name suggests, sets up the world that the characters live in, introduces

the characters themselves, and begins to lay down the conflict that drives the story

onwards (Moura, 2014). The second act tends to focus on the main character “pursuing their objective while coping with a

series of obstacles” (Strathy, 2008). Meanwhile, tension increases in

relation to the crisis. Lastly, the third act “presents the final confrontation” (Moura, 2014) and is usually the

shortest in length as the conclusion of the film is reached. The first plot

point, then, generally refers to the point at which the main character “commits to the story goal or embarks on the

journey” (Strathy, 2008) whereas the second is the point where it seems all

hope is lost and that the main character is doomed (Strathy, 2008).

The five-act structure (sometimes known

as Dramatic Structure), on the other hand, is that which was identified by

German playwright Gustav Freytag in 1863 (Smailes, 2019). As its name suggests,

it details five different acts over which a story takes place; act 1 is the ‘Exposition’,

act 2 is ‘Rising Action’, act 3 is the ‘Climax’, act 4 is ‘Falling Action’, and

the final and fifth act is that of ‘Dénouement’. Freytag produced a pyramid to

illustrate such a structure (Hellerman, 2019):

Fig. 3: Freytag’s pyramid (2019).

These acts refer to specific points in

the story just as the three-act structure does. In this case, the Exposition is

the setting up of the characters, world, and inciting incident that spurs to

beginning of the story, the Rising Action is the obstacles that the main character

encounters on their way in attempts to resolve the aforementioned inciting

incident, and the climax is the “highest

point of tension” (Smailes, 2019). This tends to be where the ‘showdown’

scene happens, followed by the Falling Action that highlights the calm after

the climax as the story progresses towards its conclusion. Finally, Dénouement

occurs when “conflicts are resolved and

loose ends tied up” (Smailes, 2019).

Accompanying these act structures are different

plot types and ending types. The three main types of plot are as follows; the

Arch plot, the Mini-plot, and the Anti-plot. The arch plot is considered to be

the " classic plot” (Bevis, 2017)

as the protagonists have a goal that they are attempting to achieve by the end

of the story and are driven by external conflict that gives rise to change

(Cross, 2018). Mini-plots focus mainly on internal conflicts wherein the main character

battles their “inner demons” (Cross,

2018), and anti-plots are those concerned with fractured narratives and an

unchanging protagonist (if such a title can even be applied to characters in an

Anti-plot) (Bevis, 2017). These avoid linear plots and definitive purposes; there

is no conflict, no clear-cut timeline, no protagonists or antagonists, and no other

type of driving force behind such a plot (Cross, 2018).

As for ending types, there are three

main ones: closed endings, open endings, and partial endings. Closed endings

are those which resolve all aspects to a plot; there are no plot threads left open,

and in some cases, there is no future left for the characters to pursue as an

entirely conclusive end is reached (Gurskis, 2006). Open endings, on the other

hand, are those which leave conflicts mostly or wholly unresolved. No definite

resolution is reached, and the audience is usually left to interpret it however

they like (Gurskis, 2006). Partial endings, then, are those that see all story

arcs completed but there is still an opportunity for future endeavours to

happen, as is the case with a lot of media.

Monsters,

Inc. could arguably fit both the three and five-act structures. Looking

at the third-act structure first, though, sees the first act, or the setup,

occurring with the establishing of the factory and the city that Mike and Sulley

live in as well as the characters themselves. The film makes note of the energy

crisis that the monsters are facing and that the monsters are led to believe

that human children, the source of their energy, are toxic. This act focuses on

the more mundane side of Mike and Sulley’s life as it delves into their daily routine

as workers in the factory as well as at home.

Fig. 4: The first act of the film

(when considering both the three and five-act structures) is dedicated to

setting up the world that Mike and Sulley live in. In this case, it’s the city

of Monstropolis (2001).

The second act, or confrontation, begins

with the first plot point kicking in when it’s revealed that Randall has been

cheating in order to boost his numbers to beat Sulley out of the ‘top scarer’

spot; Sulley stays behind to file paperwork for Mike and encounters the door

that Randall leaves on the ground floor, and as a consequence, meets Boo. This

leads to Sulley ruining Mike’s date with his girlfriend and accidental exposure

of the escaped human child to the general public, thus putting the company at

risk. Sulley and Mike then spend most of this act trying (and failing) to return

Boo to her door, all the while being antagonised by Randall and the

difficulties of concealing Boo’s identity. This continues up until the second plot

point wherein Mike and Sulley are banished, and it seems like they are going to

fail their objective.

Fig. 5: At the end of the three-act structure’s

second act, the scene where Mike and Sulley are banished to the human world fits

with the concept of the second plot point wherein the protagonists believe that

their endeavours are hopeless (2001).

The third act comes when the final conflicts

come into play with both Randall and Waternoose, and a resolution is reached.

After Randall and Waternoose’s scheme is unveiled, the plot becomes high in

tension Randall is defeated by Mike, Sulley, and Boo, and the three of them expose

Waternoose, prompting his arrest and the company falling into Sulley’s hands

after they return Boo to her door. Later, the energy crisis is solved when the

laughter of human children is used as a replacement to screams, and Mike pieces

together Boo’s door so Sulley can reunite with her.

The film, then, could be broken down

further to fit the five-act structure. The first and second acts, the exposition

and rising action respectively, are similar to the three-act structure’s first

two acts as they establish the world and its characters, initiate the inciting incident,

and the conflict begins. The climax could also fit with the third act of the

three-act structure, as the highest point of tension in the film could be said

to be the scene in which Waternoose is pursuing Sulley and Boo through the

corridors and attempting to break down the door as Sulley tries to send Boo

home moments before they and Mike expose Waternoose’s plans.

Fig. 6: The five-act structure would likely see the film’s most high-stakes and high-tension scene being that when Waternoose pursues Sulley and Boo and attacks them both, before promptly having his plan of keeping the company afloat no matter the sacrifice exposed (2001).

The fourth act or falling action then

follows on from this and is the immediate relief of the previous scene. Mike’s Manager

and head of the Child Detection Agency Roz alerts them that Waternoose has been

arrested and lets Mike and Sulley send Boo off in peace. They then leave the factory

to see the commotion outside, and Mike plants the idea of laughter as a substitute

for screams in Sulley’s head.

Therefore, the fifth act, or dénouement,

is the final set of scenes which illustrate Sulley working as the company’s new

chairman with the idea from the previous scene now fully operational as the

factory’s main and only way of generating energy; as a result, it has solved

the energy crisis. It also encompasses the scene where Mike reveals that he pieced

Boo’s door back together and encourages Sulley to put in the final piece so

they can see each other again.

Fig. 7: The dénouement sees the

changes taking place in the factory; Sulley is now its chairman in place of

Waternoose, and the energy is sourced from laughter rather than fear (2001).

As for ending types, Monsters, Inc. fits that of the typical ‘partial

ending’ structure. This is because while all of the plot threads are eventually

resolved by the end of the film, there is still the opportunity for a continuation

of the story by other means involving opening of potential new plot threads –

life goes on for the characters, and all of the issues opened up at the beginning

of the film are concluded. The final scene wherein Sulley opens Boo’s door and

sees her again is the final plot thread concluded as they meet again, but it

also holds potential for future adventures or storylines to arise.

Fig. 8: Sulley is reunited with Boo

in the closing scene of the film, simultaneously giving it a partial ending and

resolving the final plot thread of Sulley wishing to see her again (2001).

When looking at different plot types,

it becomes clear that Monsters, Inc. is

a film with an arch plot, since the story ends with the main characters having

faced and resolved multiple external conflicts as well as being changed and

experienced growth.

To conclude, it could be said that

Monsters, Inc. is a film that, theoretically, could work well when broken into both

the three and five-act structures.

However, it is notable that the fourth and fifth acts of the five-act structure

make up a marginal portion of the film in comparison to the first three acts, whereas

when considering the film through the lens of the three-act structure, there is

a slightly more even split between acts (loosely, when accounting for the fact

that the second act is indeed double the length of the first and third in

accordance with Field’s proposal). At the very least, it could be considered

almost definite that Monsters, Inc. suits the ‘arch plot’ and ‘partial ending’

facets of structure.

Illustration List:

- Fig. 1: Theatrical release poster for Monsters, Inc. (2001). [Poster for Monsters, Inc. (2001), dir Pete Docter.] [Online] At: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0198781/mediaviewer/rm2785401856 (Accessed 24 October 2019)

- Fig. 2: A diagram of Field’s three-act structure (2008). [Image] [Online] At: https://www.how-to-write-a-book-now.com/Syd-Field.html (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Fig. 3: Freytag’s pyramid (2019). [Image] [Online] At: https://brittanyekrueger.com/tag/freytags-pyramid/ (Accessed 27 October 2019)

- Fig. 4: The first act of the film (when considering both the three and five-act structures) is dedicated to setting up the world that Mike and Sulley live in. In this case, it’s the city of Monstropolis (2001). [Film still from Monsters, Inc. (2001), dir. Pete Docter] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/monsters-inc-2001/6/#box-1/41/monsters-inc-disneyscreencaps.com-941.jpg?strip=all (Accessed 27 October 2019)

- Fig. 5: At the end of the three-act structure’s second act, the scene where Mike and Sulley are banished to the human world fits with the concept of the second plot point wherein the protagonists believe that their endeavours are hopeless (2001). [Film still from Monsters, Inc. (2001), dir. Pete Docter] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/monsters-inc-2001/39#box-1/42/monsters-inc-disneyscreencaps.com-6882.jpg?strip=all (Accessed 27 October 2019)

- Fig. 6: The five-act structure would likely see the film’s most high-stakes and high-tension scene being that when Waternoose pursues Sulley and Boo and attacks them both, before promptly having his plan of keeping the company afloat no matter the sacrifice exposed (2001). [Film still from Monsters, Inc. (2001), dir. Pete Docter] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/monsters-inc-2001/51#box-1/48/monsters-inc-disneyscreencaps.com-9048.jpg?strip=all (Accessed 27 October 2019)

- Fig. 7: The dénouement sees the changes taking place in the factory; Sulley is now its chairman in place of Waternoose, and the energy is sourced from laughter rather than fear (2001). [Film still from Monsters, Inc. (2001), dir. Pete Docter] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/monsters-inc-2001/56#box-1/35/monsters-inc-disneyscreencaps.com-9935.jpg?strip=all (Accessed 27 October 2019)

- Fig. 8: Sulley is reunited with Boo in the closing scene of the film, simultaneously giving it a partial ending and resolving the final plot thread of Sulley wishing to see her again (2001). [Film still from Monsters, Inc. (2001), dir. Pete Docter] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/monsters-inc-2001/57/#box-1/17/monsters-inc-disneyscreencaps.com-10097.jpg?strip=all (Accessed 27 October 2019)

Bibliography:

- Bevis, K. (2017), Arch Plot, Mini-plot, and Anti-plot. [Online] At: https://kaitlinbevis.com/2017/03/29/arch-plot-mini-plot-and-anti-plot/ (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Cross, J. L. (2018), Writing A Novel: Arch-Plot Vs Mini-Plot — What’s The Difference? [Online] At: https://medium.com/@liamjcross22/writing-a-novel-arch-plot-vs-mini-plot-whats-the-difference-801189119721 (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Cross, J. L. (2018), Writing A Novel: What Is An Anti-Plot? [Online] At: https://medium.com/@liamjcross22/writing-a-novel-what-is-a-anti-plot-fb2c57763254 (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Gurskis, D. (2006), The Short Screenplay: Your Short Film from Concept to Production (Aspiring Filmmaker's Library). Boston: Thompson Course Technology PTR. Page 58.

- Hellerman, J. (2019), What is Five-Act Structure and How Do You Use It? [Online] At: https://nofilmschool.com/how-to-write-five-act-structure (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Moura, G. (2014), The Three-Act Structure. [Online] At: http://www.elementsofcinema.com/screenwriting/three-act-structure/ (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Smailes, G. (2019), The Importance of Structure When Writing Your Novel. [Online] At: https://bubblecow.com/blog/importance-of-structure (Accessed 26 October 2019)

- Strathy, C. G. (2008), Syd Field's Model of Screenplay Structure. [Online] At: https://www.how-to-write-a-book-now.com/Syd-Field.html (Accessed 26 October 2019)

Friday 25 October 2019

Collaboration: Waiter Design

Since our skits include a waiter character who appears briefly, I made three quick designs using typical waiter outfits as a reference.

After speaking to the studio, we agreed on the second outfit combined with the third hairstyle. I went back to see what this would look like and refine it a little, and ended up with the final design for the character;

Collaboration: Set Design (Part 4)

After the group received our OGR feedback, I used it to revisit the design of the restaurant. Since Alan suggested replacing the multiple smaller lights with something that would create a spotlight effect above the table to highlight the characters, I used one larger light centred above the table.

To see what this would hopefully look like, I made a second version of the bottom image and experimented with darkening the background and drawing on the lighting to create the first image.

I also removed some of the finer details from the background as to not overcomplicate the design too much and draw the audience's attention elsewhere.

Thursday 24 October 2019

Film Reviews: Coco (2017) and Archetypes

Fig. 1: Theatrical release poster for Coco (2017).

This review will be investigating

Christopher Vogler’s and Carl Jung’s archetype theories within Lee Unkrich’s Coco (2017), an animated film inspired

by the Day of the Dead holiday originating in Mexico. The story is about

Miguel, a young boy who dreams of becoming a musician in spite of his family’s

banning of all types of music. Miguel, following a turn of events involving a

dispute with his family and stealing a famous musician’s guitar, ends up

transported to the Land of the Dead in which he must find his

great-great-grandfather to enlist his help in a bid to not only return home,

but to achieve his dream.

Swiss Psychoanalyst Carl Jung

theorized that archetypes are “unconscious

images of the structures and patterns of human behaviour” (Blair, 2019) –

this means that Jung believed they were fundamental aspects of everyone’s

personality, and categorized them into the Persona, the Shadow, the Anima or

Animus, and the Self (Cherry, 2019). These are essentially how one presents

themselves to the world and particular groups of people, the repressed desires

and instincts that one keeps within as they are unacceptable to exhibit

publicly, the masculine image in the feminine psyche or the feminine image in

the masculine psyche, and finally, the unification of both consciousness and

unconscious images within an individual (Cherry, 2019). From these four basic

archetypes, writers have gone on to identify numerous other archetypes and

patterns in storytelling across time such as Vladimir Propp’s archetypal

characters and situations, Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey, and

Christopher Vogler’s archetypes (Blair, 2019) amongst others.

In his book The Writer’s

Journey (2007), Christopher Vogler wrote about eight major archetypes “common

to storytelling and most strongly associated with Campbell’s monomythic

structure” (Blair, 2019), including the Hero, Herald, Threshold Guardian,

Shapeshifter, Shadow, Mentor, Ally, and Trickster archetypes. These are

sometimes accompanied by other archetypes as well, such as the Mother, Father,

Child, and Maiden amongst others, though these are more rooted in Jungian

psychology (Blair, 2019).

The hero or heroine of a story tends

to be the “classic protagonist” (Straker, 2002) driven by aspirations

and transforming in terms of personal growth after facing personal struggles

and obstacles throughout a story; they also have a tendency to begin their

journey as an ordinary person that the audience can project onto (Straker,

2002). In Coco, this archetype is fulfilled by protagonist Miguel

Rivera, who dreams of becoming a musician against his family’s wishes and bound

by a rule that bans all music due to his great-great-grandfather’s apparent

abandonment of his family for it. Upon being transported to the Land of the

Dead, Miguel eventually faces up to his personal and familial struggles by

uncovering the secrets of his great-great-grandfather – having been lead to

believe that beloved musician Ernesto de la Cruz was his

great-great-grandfather, Miguel discovers that it was in fact Héctor Rivera,

and that Ernesto had stolen Héctor’s music for his own gain. By the end of the

film, Miguel has managed to overcome his own shortcomings, save and reunite

Héctor with his wife Imelda and eventually their daughter Coco, and lift the

family’s restrictions on music.

In this instance, then, the

shadow archetype is fulfilled by Ernesto de la Cruz. The shadow usually provides

the Hero with their “main and most dangerous obstacle” (Bernstein, 2018)

or they can manifest as “darker qualities of the Hero’s personality or

unrealized or rejected aspects of the self” (Bernstein, 2018). Ernesto

initially welcomes Miguel in attempts to gain his trust and later reveals that

his intentions were malicious after having poisoned and murdered Héctor and

profiting off of the lyrics and music that he’d written and later trying to

attack the Riveras and throwing Miguel off of a platform.

Fig. 2: Ernesto de la Cruz is

revealed to be the ‘shadow archetype’ of the movie after Miguel learns the

truth about Héctor’s fate (2017).

The herald tends to prompt the

beginning of the hero’s journey by either directly or indirectly announcing

important information or leading to a revelation (Straker, 2002). For Miguel, this

is the photograph that falls off of the family’s ofrenda (offerings placed onto

a ritual display as part of Day of the Dead celebrations); the frame that it is

in breaks upon hitting the floor and Miguel discovers that it has been

purposely folded to conceal his great-great-grandfather out of sight. Not only

that, but the face has been torn off prior to its discovery leaving only his

great-great-grandmother Imelda and great-grandmother Coco intact. This leads

Miguel to believe that, since the man in the photograph is holding what is

assumed to be Ernesto’s guitar, that not only was he a musician, but that it

was Ernesto himself, serving as the catalyst for Miguel defying his family.

Fig. 3: The photograph of Imelda,

Coco, and Héctor Rivera that had Héctor’s face torn out is what led to the

beginning of Miguel’s journey (2017).

Threshold guardians are considered

to be characters that “serve as

opportunities for the Hero to test their abilities and grow in strength” (Bernstein,

2018) and are often represented through “lesser

villains, natural forces, puzzles or sentinels” (Bernstein, 2018) and may

eventually end up as allies (Blair, 2019). For Miguel, these threshold

guardians likely take the form of Imelda and her spirit guide (also known as an

alebrije) Pepita, alongside the rest of the Rivera family residing in the Land

of the Dead; this includes Rosita, Victoria, Julio, and twins Oscar and Felipe.

They present the challenge of pursuing Miguel and Héctor through the Land of

the Dead, forcing them to constantly keep out of sight as their goal is to

return Miguel home against his wishes. As the definition suggests, these

characters eventually become allies and help Miguel and Héctor stave off Ernesto’s

guards (who in themselves could be considered threshold guardians but are much

less prominent in their roles).

The trickster archetype

tends to be one that provides comic relief to the audience through means of

mischief, and their allegiance can vary as can their intelligence; they are

just as likely to be in cahoots with a shadow archetype or a hero archetype,

and some have the ability to impart wisdom whereas others are simply mischievous

(Straker, 2002). Overall, though, it can be assumed that this character serves

as a means of causing change, usually while remaining totally unaffected (Blair,

2019). In Coco, this character could be

assumed to be Dante, Miguel’s stray dog companion who accompanies him to the Land

of the Dead. At the beginning of the film, Dante is considered a nuisance by

Miguel’s Abuelita Elena due to the mischief and mess that he creates; for the

rest of the film, Dante acts as a form of light-hearted comedy relief but is

simultaneously useful upon the reveal that he is Miguel’s alebrije – he also

remains ultimately unaffected by either the plot or the chaos he causes.

Fig. 4: Dante

serves as comedy relief as well as becoming Miguel’s spirit guide (2017).

Mentor types are

often the protector and teacher of the hero, giving them the guidance and

skills necessary for them to achieve their goal (Bernstein, 2018). They’re also

typically older and smarter than the hero, as “as they offer their superior knowledge and experience in support”

(Straker, 2002). It could be argued that Héctor serves as Miguel’s mentor, since

not only is he much older, he guides Miguel through a large portion of the film

(although he could be considered to be an unconventional mentor when accounting

for his much more chaotic side, mostly shown at the beginning of the film when

attempting to access the Land of the Living and wreaking havoc). Overall, Héctor’s

main goal other than to see his daughter is to escort Miguel to Ernesto before

the reveal that he is actually Miguel’s relative instead, and, as such, helps

Miguel disguise himself and move from place to place undetected. One specific

example of Héctor acting as a mentor would be the scene wherein Miguel must

perform on stage, and Héctor advises him on how to do so by using his own

experience.

Ally characters function mostly as

the hero’s companions and aid them on their journey. Oftentimes, they are able

to approach situations from perspectives that the hero might not have been able

to come across by themselves (Blair, 2019). Miguel’s allies, in this case, are

his family in the Land of the Dead as well as Dante. The former transition from

threshold guardian types to allies towards the end of the film, whereas the

latter is established as one early on and remains so for the rest of the story.

They assist Miguel to varying degrees, but they all band together to take down

Ernesto, save Héctor from fading away permanently, and to get Miguel and Dante

home.

Fig. 5: The Rivera family

residing in the Land of the Dead initially act as threshold guardians towards Miguel

but become allies by the end of the film (2017).

The mother archetype tends to reference

those which display typically maternal love and become a mother-like figure if

they are not directly related to the hero already (Butler-Bowdon, 2017). In the

case of Coco, it seems that Miguel’s Abuelita Elena fits this role more than

any other character. Asides from the fact that she is his grandmother, she acts

as the stern mother figure throughout the film and claims that her motives are what

is best for Miguel (specifically referencing the destruction of his instrument in

attempt to maintain the family’s long-standing ban on music) and treats him

with an overbearing tenderness. To a much lesser extent, Miguel’s actual mother

Luisa fulfils this role – she is much kinder and softer in approach than Elena,

but she appears much less frequently and has less of an influence on the story

or Miguel himself.

The father archetype, similar to

the mother archetype, typically functions as one that is parental. However, in a

contrast to the nurturing mother, the father tends to be somewhat more authoritative

with a knack for intellect and will (Kushner, 2018) and seem to have traits

overlapping with that of the mentor archetype. In Coco, the father seems to be Héctor, who is Coco’s father and acts

much like a father figure to Miguel, offering advice and assistance (again melding

with the mentor traits that he possesses as well). Héctor is notably desperate

to return to Coco as the family was under the impression that he had abandoned

them for the life of a musician even though this wasn’t the case. Again, to a

lesser extent, the father could also be Miguel’s father, Enrique, as he is literally

the paternal figure in Miguel’s life and maintains an authoritative approach.

Child archetypes are those revolving

around the innocent, as well as “dependency

and responsibility” (Givot, 2009). These do not always have to be a child,

however, just as the father and mother archetypes are not always representative

of a literal scenario – this could be applied to Coco with the titular character; due to her age, she is very much

dependent on her family and has an air of innocence about her due to her

apparent obliviousness to her surroundings and failing memory. In a literal

sense, she is the child of Héctor and is seen as such in multiple flashback

sequences involving her as a toddler. The archetype could also apply literally

to Miguel who is a child in the present and is dependent upon the adults in his

life to allow him to pursue his dream as well as to protect him and bestow upon

him the blessing needed to return home.

Fig. 6: Héctor and Coco share a

father-daughter relationship, shown initially through a flashback sequence

before they are reunited at the end of the film (2017).

The maiden archetype relies on

traits of innocence, desire, and purity (Cherry, 2019) to be displayed and it

is traditionally applied to feminine characters (love interests in particular).

This archetype is somewhat difficult to pinpoint within Coco due to the lack of a prominent ‘damsel in distress’ type character

but could arguably be applied to Imelda as she and Héctor are separated until

the end of the film wherein they become each other’s love interests once more,

and she exhibits a softer or ‘purer’ side again shown in the second half of the

film.

Finally, the shapeshifter represents

“uncertainty and change, reminding [the

audience] that not all is as it seems” (Straker, 2002). These characters

can be thought of as untrustworthy as they can switch allegiances or it is unclear

which they belong to; while they are generally mysterious, however, the

archetype can be applied to characters that are considered both good and bad

(Bernstein, 2018). In the latter sense, this role could be filled by Ernesto,

as he is initially a revered musician and treats Miguel like family without

question but is quick to show his true colours and reveals himself as having

malicious intent both in the past and present with the murder of Héctor and

theft of his music and attacking the Riveras. In the former sense (and much

more literally), the shapeshifter archetype could apply to Dante. His

importance increases upon officially transforming into Miguel’s spirit guide.

Fig. 7: The truth behind Ernesto’s

motives are revealed towards the end of the film (2017).

To conclude, numerous different

archetypes including those coined by Vogler and Jung could be applied to the

characters within Coco as their

personality traits, how they interact with one another, and their roles within

the story at large evidence this.

Illustration List:

- Fig. 1: Theatrical release poster for Coco (2017). [Poster for Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2380307/mediaviewer/rm585455872 (Accessed on 20 October 2019)

- Fig. 2: Ernesto de la Cruz is revealed to be the ‘shadow archetype’ of the movie after Miguel learns the truth about Héctor’s fate (2017). [Film still from Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/coco-2017/56/#box-1/42/coco-disneyscreencaps.com-9942.jpg?strip=all (Accessed on 23 October 2019)

- Fig. 3: The photograph of Imelda, Coco, and Héctor Rivera that had Héctor’s face torn out is what led to the beginning of Miguel’s journey (2017). [Film still from Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://vignette.wikia.nocookie.net/cocomovie/images/5/5f/Hector_and_family.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20181107232310 (Accessed on 23 October 2019)

- Fig. 4: Dante serves as comedy relief as well as becoming Miguel’s spirit guide (2017). [Film still from Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/coco-2017/50/#box-1/18/coco-disneyscreencaps.com-8838.jpg?strip=all (Accessed on 23 October 2019)

- Fig. 5: The Rivera family residing in the Land of the Dead initially act as threshold guardians towards Miguel but become allies by the end of the film (2017). [Film still from Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2380307/mediaviewer/rm3524493056 (Accessed on 23 October 2019)

- Fig. 6: Héctor and Coco share a father-daughter relationship, shown initially through a flashback sequence before they are reunited at the end of the film (2017). [Film still from Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2380307/mediaviewer/rm1522882048 (Accessed on 23 October 2019)

- Fig. 7: The truth behind Ernesto’s motives are revealed towards the end of the film (2017). [Film still from Coco (2017), dir. Lee Unkrich] [Online] At: https://animationscreencaps.com/coco-2017/44/#box-1/23/coco-disneyscreencaps.com-7763.jpg?strip=all (Accessed on 23 October 2019)

Bibliography:

- Bernstein, R. (2018), Archetypal Characters in the Hero’s Journey. [Online] At: https://online.pointpark.edu/screenwriting/archetypal-characters-heros-journey/ (Accessed on 20 October 2019)

- Blair, J. (2019), Essential Archetypes. [Online] At: https://storygrid.com/essential-archetypes/ (Accessed on 20 October 2019)

- Butler-Bowdon, T. (2017), 50 Psychology Classics: Your shortcut to the most important ideas on the mind, personality, and human nature. [Online] At: http://www.butler-bowdon.com/carl-jung---the-archetypes-and-the-collective-unconscious.html (Accessed on 21 October 2019)

- Cherry, K. (2019), The 4 Major Jungian Archetypes. [Online] At: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-are-jungs-4-major-archetypes-2795439 (Accessed on 21 October 2019)

- Givot, J. (2009), The Child Archetype. [Online] At: http://archetypist.com/2009/11/24/the-child-archetype/ (Accessed on 22 October 2019)

- Kushner, M. D. (2018), Fathers: Heroes, Villains, and Our Need for Archetypes [Online] At: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/transcending-the-past/201805/fathers-heroes-villains-and-our-need-archetypes (Accessed on 22 October 2019)

- Straker, D. (2002), Vogler’s Archetypes. [Online] At: http://changingminds.org/disciplines/storytelling/characters/vogler_archetypes.htm (Accessed on 20 October 2019)

Wednesday 23 October 2019

Toolkit 2: Character Design: Session 3

In this week's character design session, we started to look at set design including both the exterior and the interior of a building. To begin with, we were given a famous building and a theme that we could apply to it. I was given the Guggenheim Museum and my theme was steampunk.

I started off by looking at the building itself to understand the basic shapes before putting the theme onto it.

After some feedback from Justin, I went back and drew it again to revisit the original shapes of the building in a slightly better way so it was still completely recognisable.

We then moved on to looking at the interior of the building we'd designed, while also keeping to the theme we'd been given beforehand. I was struggling with the perspective and how to incorporate the ring shape from the outside of the building into the roof as well as the vast expanse that should've been on the floor so Justin provided me with sketches to help me to understand it better.

For the rest of the morning I carried on looking at the interior and what the different angles would show or what could be put into the inside of the bottom floor (such as a machine in the centre, elevators or machines around the edge of the wall).

In the afternoon, we went back to our personal character design projects. Since my set theme was '1930's/40's Hollywood', I began referencing some images I'd found but focused mainly on the composition of the pictures.

I also revisited some of the objects I'd been looking at before such as the vinyl toys including dolls and cars. After speaking to Justin again, it seems like the sequence that I'm going to have to consider later on ('entering a room' and 'the big shootout') are going to take place in typical gangster-style settings such as a back alley leading to some kind of club or other venue. Justin suggested having a shot at the beginning to set the scene that would incorporate the old-fashioned 'Hollywood glam' style with the use of a shot of the city skyline.

Monday 21 October 2019

Toolkit 2: Drawing: Session 3

Today's life drawing lesson started out with some quick poses where we tried different methods of linework. The first and last poses had us drawing however we wanted, whereas the second pose (which I drew twice) had us considering exactly how many marks we were making on the page; we had to limit the amount of strokes we used to suggest the figure. The third pose was a continuous line drawing, and the fourth was a variation of this; we were limited to using vertical and horizontal lines only (or as close as we could get), in essence recreating an 'etch-a-sketch' style thereabouts.

The next poses were 30 minutes long and had us looking at how the light affected the model. The first pose was done with the light on, and the next was done with the light on for the first half (so we could look at the basic form of the model) and off for the second.

The last pose was a relatively short one. I used the time to try and work bigger and more loosely as that's something I need to work on.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-

Fig. 1: Theatrical release poster for Coco (2017). This review will be investigating Christopher Vogler’s and Carl Jung’s archetype...

-

Fig. 1: Edward Scissorhands Poster (1990) This review will focus on Tim Burton's Edward Scissorhands (1990) and how the concept...

-

Fig. 1: Theatrical release poster for Treasure Planet (2002). Ron Clements and John Musker’s Treasure Planet (2002) is an animated s...